The inner space race: then and now

Sixty years ago today (23 January), Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh climbed into an undersea craft called the Trieste and dived nearly 11 kilometres down to the deepest point in the ocean – the “Challenger Deep” of the Mariana Trench in the Pacific. Piccard and Walsh are much less well-known than the first astronauts who walked on the Moon, and the story of the earlier deep-sea pioneers whose achievements led to their dive is seldom told. So who were the first “bathynauts” to visit the ocean depths – and how does their “inner space race” still resonate today?

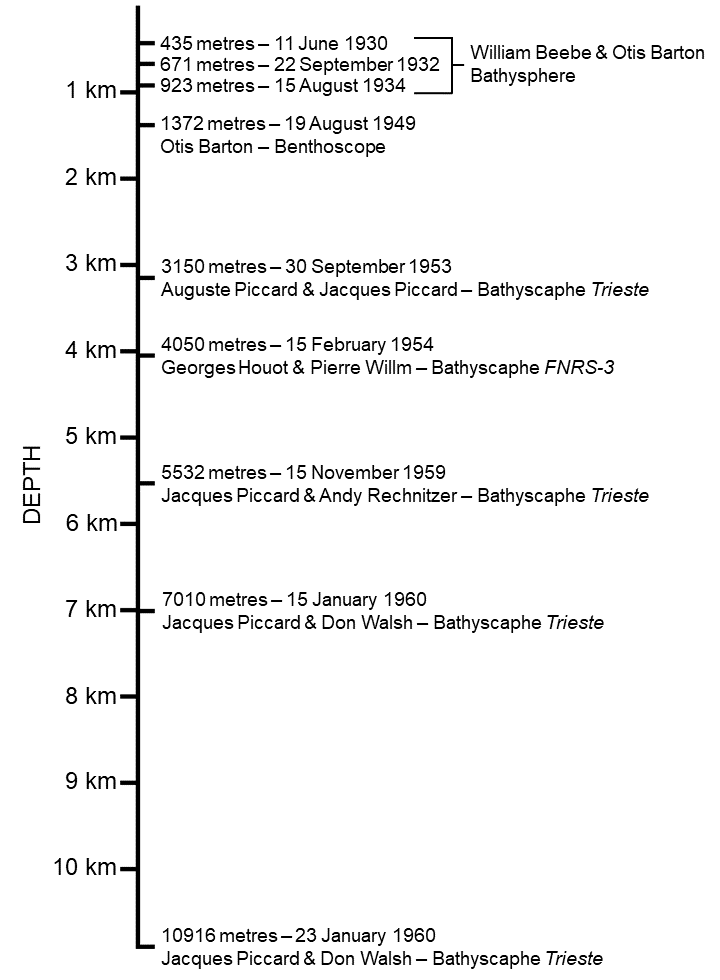

William Beebe and Otis Barton became the first bathynauts in the early 1930s, diving in the “bathysphere” that Barton designed. In common with later deep-sea vehicles, the bathysphere had a strong hull to resist the pressure of the deep ocean, allowing those inside to remain at normal atmospheric conditions and avoid the need to decompress like SCUBA divers. Beebe and Barton dived to 435 metres deep in the bathysphere in 1930, and in 1932 they broadcast live from 671 metres deep to listeners of NBC and BBC radio across the US and Europe. Finally in 1934 they reached 923 metres deep, as Beebe described in his book “Half Mile Down”.

Beebe and Barton's colleague Gloria Hollister became the first female bathynaut, diving to 368 metres in the bathysphere in 1934. Hollister remained the world’s deepest diving woman for several decades, as naval traditions that excluded women from submarines spilled over to ocean exploration during the Cold War. Meanwhile Barton went on to design another craft called the “benthoscope” to venture deeper than the bathysphere, and on 19 August 1949 he set a new depth record of 1372 metres inside it.

The bathysphere and benthoscope both dangled on a cable from a ship above, which limited their manoeuvrability. But Swiss physicist and inventor Auguste Piccard, who had soared to record-breaking altitudes in the pressurised gondola of a balloon in the early 1930s, realised that the principles of an airship could be adapted to create a new type of undersea vehicle. Instead of using a cable to lower and raise the craft, Piccard’s “bathyscaphe” used ballast weights and a buoyancy tank filled with lighter-than-water petrol, similar to the helium-filled envelope of an airship.

The first bathyscaphe was ready for testing in 1948, and Piccard named it the “FNRS-2” after Belgium’s Fonds National de la Researche Scientifique (FNRS), who paid for it. Unfortunately the FNRS-2 ran into difficulties after an unoccupied test dive to 1400 metres deep, preventing a deep dive with people aboard during that year.

Piccard asked for more funds for another attempt, and his Belgian backers struck a deal with the French Navy, who were interested in developing the bathyscaphe further, eventually christening the rebuilt craft “FNRS-3”. But Piccard went his own way, working with his son Jacques to raise money from European industrialists for a new bathyscaphe, which they named the “Trieste”. On 30 September 1953 father and son set a new depth record of 3150 metres in the Trieste – and Auguste Piccard become the first person to explore the stratosphere and the deep ocean.

The French Navy pipped the Piccard’s record on 15 February 1954, reaching 4050 metres with Georges Houot and Pierre Willm in the bathyscaphe FNRS-3. Houot wrote one of the first articles in the scientific literature about using a bathyscaphe for ocean research, published in volume 2 of the journal Deep-Sea Research in 1955. Willm later designed the bathyscaphe Archimède, which made several dives into ocean trenches during the 1960s, and took people to the undersea volcanic rift of the mid-ocean ridge for the first time in 1973.

By the mid-1950s the Piccards were hunting for further funding to develop and operate the Trieste, and the craft caught the attention of geologist Robert Dietz, who was working for the US Office for Naval Research. Dietz invited Jacques Piccard to give a talk in Washington DC on 29 February 1956, where 103 scientists were meeting to discuss the potential of deep-diving vehicles for ocean research. The Office for Naval Research subsequently chartered the Trieste for a series of science dives in the Mediterranean in 1957 – and the Piccards sold the Trieste to the US Navy in 1958, on the condition that Jacques would continue to operate it. The US Navy set the goal of using the Trieste to reach the deepest point in the ocean, which they achieved on 23 January 1960 with Jacques and Lieutenant Don Walsh aboard.

Unlike astronauts, the story of the early bathynauts began before the competition of Cold War superpowers, and was driven more by private individuals such as Beebe, Barton, and the Piccards. After the record-setting plunge of 1960, deep-diving vehicles became a matter of national capability for science and strategic purposes, and they remain so for some nations today. But private citizens have become involved again: Hollywood director James Cameron returned to the Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench in 2012, and billionaire Victor Vescovo and his expedition team dived there several times in a new vehicle last year.

There is another kind of “inner space race” taking place today, where governments are seeking to extend their rights to ocean resources and stake claims for future deep-sea mining in areas beyond national boundaries. Thanks to remote specks of Overseas Territories such as the Pitcairn Islands, the UK has the world’s fifth largest “Exclusive Economic Zone” of rights to ocean resources – approximately 27 times larger than the UK’s land area – along with licences from the United Nations to explore for manganese nodules in 133,539 km2 of the eastern Pacific. Sixty years after the Trieste dived to the Challenger Deep, the capability to reach anywhere in the deep ocean may be quietly redrawing the geopolitical map for the future.

Jon Copley, January 2020

A later version of this became an article published by The Conversation

| Previous | Index | Next |